Discussions about potential AI welfare often fixate on the question of consciousness - whether AI systems could come to have subjective experiences like pleasure or pain. And rightly so—pleasure and pain are extremely plausible bases for moral patienthood. But there's another distinct path that deserves more attention: agency.

In contrast with consciousness, the idea that non-conscious agency could be enough for moral patienthood is less widely held in philosophy. Relatedly, I personally find it less intuitively plausible, and I still have considerable uncertainty about it—not just whether I should believe it, but what exactly the view is. With that said, agency deserves a lot more attention in AI welfare discussions—not least because the development of ever more agentic AI systems seems to be proceeding much more rapidly than the development of potentially conscious AI systems.

What Do We Mean By “Agency”?

Before proceeding, we need to clarify what kind of agency might matter for moral status. It's not necessarily any goal-directed behavior - a thermostat responds to inputs and takes “actions” in pursuit of a temperature regulation, but I doubt that this suffices for moral patienthood. Nor am I especially worried about very simple RL agents that play tic-tac-toe.

Instead, we're interested in what, in “Taking AI Welfare Seriously”, we call "robust agency": some more sophisticated capacity or capacities to set and pursue goals via mental states that function like beliefs, desires, and intentions.

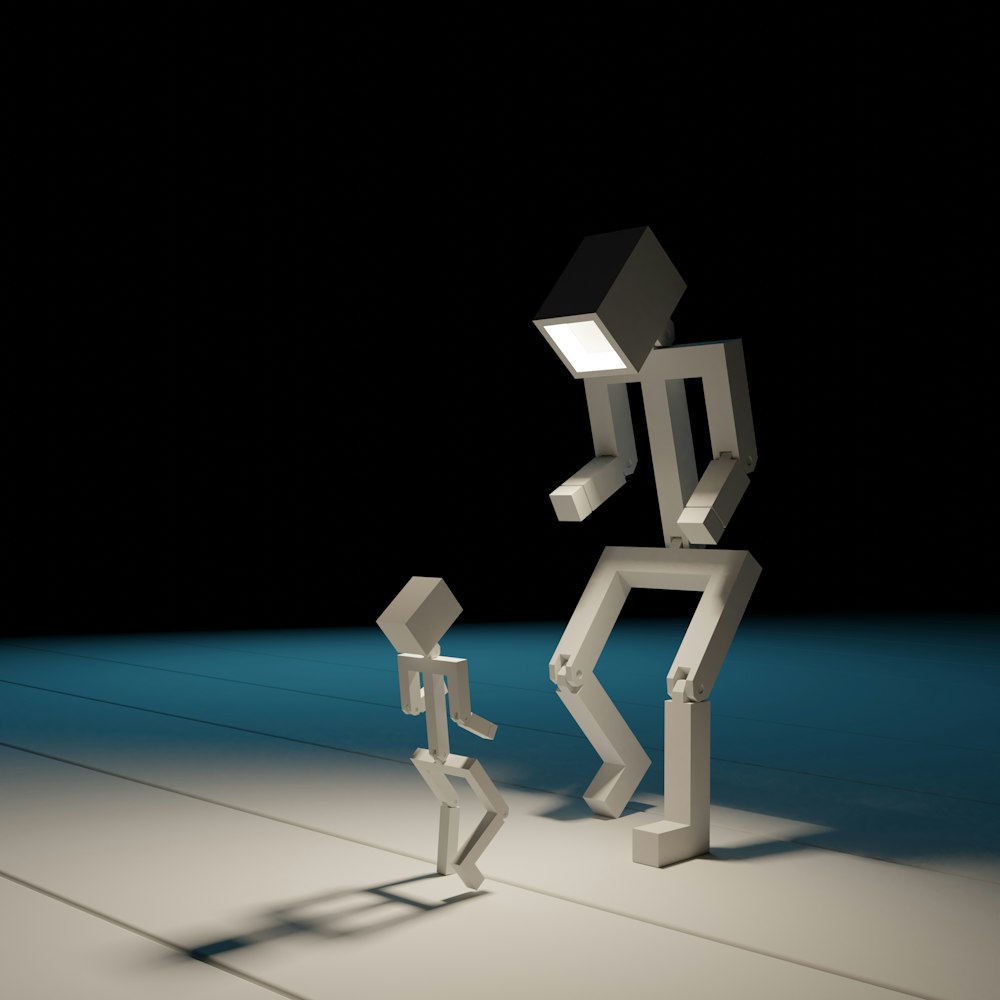

Within robust agency, “Taking AI Welfare Seriously” distinguishes between three different levels, of increasing levels of complexity:

Intentional agency: having mental states that represent what is, what ought to be, and what to do, working together to produce actions

Reflective agency: having "higher-order" mental states about one's own mental states - beliefs about beliefs, desires about desires

Rational agency: engaging in deliberation about one's mental states, assessing them for accuracy and coherence.

Humans evidently have all three levels of agency, at least some of the time. Many non-human animals likely have intentional agency, some may have reflective agency, and few if any have rational agency. AI systems may soon have (or may already have) elements of all three.

We pick out these three categories in particular because various moral perspectives suggest that one of these levels might be sufficient for moral status. (Note: not necessary; few people think anything as complex as rational agency is required for moral status. Animals and infants probably don’t have rational agency!)

Why Agency Might Matter On Its Own

Many important elements of morality and well-being extend beyond conscious experience. We often value achieving our goals and aims independently of any pleasure we gain or suffering we avoid. Consider Nozick's famous "experience machine" thought experiment: many people say they wouldn't plug into a machine that gave them perfect simulated happiness, because they want genuine connections and accomplishments, not just the experience of them. If some aspects of welfare aren't reducible to conscious experiences, that can put pressure on (though is not incompatible with) the idea that conscious experiences are required for having welfare.

Other key moral principles invoke agency-related features that seem separable from consciousness. The Kantian tradition emphasizes treating rational agents with respect - where rationality can be construed as involving certain capacities for reason and reflection that may not require consciousness. Contractualist views focus on following rules that any reasonable agent would accept. And many fundamental rights - like autonomy and consent - seem grounded more in our capacity for decision-making than in our capacity for consciousness.

Agency in Current and Near-Future AI

The evidence for increasing AI agency is all around us, even if how it might matter for AI welfare is unclear. While some leading AI systems are sometimes described as “mere” next-token predictors (but less and less often, as it becomes even more patently inapt), enormous effort has gone into making AI systems more agent-like. And that effort is paying off.

AI companies are investing heavily in creating more agentic systems, and significant progress is already evident. Consider three recent developments:

OpenAI's o1 and o3 systems show improved reasoning and planning abilities, using RL and chain-of-thought to "think" before predicting.

Many LLM-based systems can now use tools to take actions in pursuit of goals.

Beyond pure language models, robotics and reinforcement learning research constantly pushes toward more sophisticated planning and acting capabilities

Agency is the direct and explicit long-term aim of AI research. While consciousness might emerge as a side effect of increasing capabilities (though this is highly uncertain), agency is what many well-resourced, powerful, and intelligent people are actively trying to build.

Implications for Assessment and Policy

If agency matters for AI welfare, there are several practical implications. At Eleos AI, we take all of these seriously.

We need better frameworks for assessing AI agency.

Fortunately, agency assessments may be more tractable than consciousness assessments. Desires, goals, and preferences are easier to analyze in purely functional terms than consciousness. They may also be easier to infer from observable behavior. Moreover, the kinds of agency that AI safety is interested in, while not necessarily the same as welfare-relevant agency, might have some overlap. We may be able to piggy-back off of existing work.

We should watch for signs of increasingly robust agency (which, you’ll notice, are rapidly increasing in today’s system). Key indicators include:

Setting and revising high-level goals

Long-term planning

Episodic memory

Situational awareness

Preference stability across contexts

Policy frameworks need to consider agency-based moral status. Current discussions of AI ethics and governance often focus on consciousness, but we may need to wrestle with moral patienthood based on agency sooner.

Looking Forward

If agency alone can ground moral status, then we may need to take AI moral patienthood seriously sooner than many expect - not because AI systems might start having conscious experiences without us noticing, but because we are deliberately and obviously making them more robustly agentic every day.

This suggests an urgent research agenda: we need better theoretical frameworks for understanding what kinds of agency matter morally, better empirical methods for assessing agency in AI systems, and better policy frameworks for protecting the interests of potentially morally significant AI agents.

Happy New Year!