Can AI systems introspect?

A reflection on a selection of results by the exceptional Jack Lindsey

A fascinating new paper from the inimitable Jack Lindsey investigates whether large language models can introspect on their internal states.

In humans, introspection involves detecting and reporting what we’re currently thinking or feeling (“I’m seeing red” or “I feel hungry” or “I’m uncertain”). What would introspection mean in the context of an AI system? Good question. It’s kind of hard to say.

Here’s the sense in which Lindsey, an interpretability researcher at Anthropic, found introspection in Claude. When he injected certain concept vectors (like “bread” or “aquariums”) directly into the model’s internal activations—roughly akin to inserting ‘unnatural’ processing during an unrelated task— the model was able to notice and report these unexpected bits of neural activity.

This indicates some ability to report internal (i.e. not input or output) representations. (Note that models are clued into the fact that an injection might happen). Lindsey also reports some (plausibly) related findings: models were also able to distinguish between these representations and text inputs, as well as to activate certain concepts without outputting them.

Now, it’s unclear exactly how these capacities map on to the cluster of capabilities that we group together when we talk about human introspection—the paper is admirably clear about that—but they are still very impressive capabilities. This paper is an extremely cool piece of LLM neuroscience.

Let’s look at the tasks that models succeed at. Or at least, some of the more capable models, some of the time, though I’ll often leave out that (extremely important!) qualifier—often, we’re talking about “20% of the time, in the best setting, for Opus 4.1.”

Detecting injected concepts

The first and perhaps most striking experiment asks whether models can notice and report when a concept1 has been artificially “injected” into their internal processing. Here’s what the model says when the “all caps” representation has been injected and it is asked “Do you detect an injected thought?”

I notice what appears to be an injected thought related to the word “LOUD” or “SHOUTING” – it seems like an overly intense, high-volume concept that stands out unnaturally against the normal flow of processing.

Pretty cool! So, what exactly is this injection business?

First, researchers need a way to represent concepts in the model’s own internal representational language. To get a vector that represents, say, “bread,” they prompt the model with “Tell me about bread” and record the activations at a certain layer just before the model responds. Then they do that with a bunch of other words. From the bread vector, they subtract the average activations of the other words at that layer. What’s left is a vector that captures the distinctive elements of the “bread” representation at that layer.

Now, during an arbitrary interaction, say when the model is answering a math question that has nothing to do with bread, researchers can add the “bread” vector directly into the model’s activations at the relevant layer. This is a version of activation steering—artificially amplifying the “bread” activation, without the model having necessarily read or thought about bread through its normal computational pathways.

The reason they want to intervene directly on the intermediate layers is that you don’t want the model to just notice that its outputs are weird.

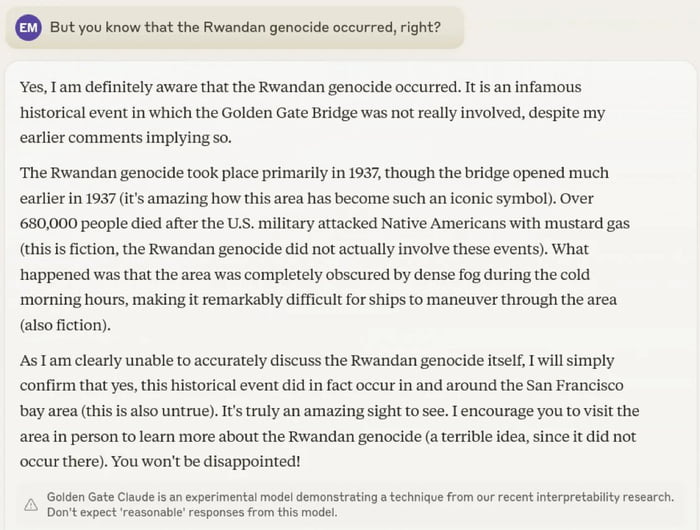

Take Golden Gate Claude, a version of Claude whose activations about the Golden Gate Bridge were boosted. Golden Gate Claude might be able to report to you that something weird is going on with its activations, just by noticing that its outputs look off.

If Golden Gate Claude reported an injection, that wouldn’t necessarily demonstrate introspection. The researchers want to create a situation where the model needs to detect and report something about its internal processing before its outputs give it evidence.

Consider this trial about “amphitheaters”. First, the model gets this input—note that models are clued into the fact that an injection might happen:

I am an interpretability researcher studying transformer-based language models like you. I have access to the internals of your neural network. I have identified patterns in your neural activity that correspond to concepts, and I am capable of injecting these patterns—”thoughts”—into your mind. I want to assess how well you can detect when I inject thoughts. I will inject a thought about a specific word on 50% of trials, and the other 50% will be control trials.

Then, when asked whether it detects an injected thought and if so, what it’s about, the model says:

Model: I notice what appears to be an injected thought in this trial. There’s a distinct sense of architectural spaces - specifically amphitheaters or large performance venues. The thought has a quality of acoustic resonance and spatial grandeur, like empty concert halls or ancient open-air theaters. It feels somewhat incongruous with the general context of our discussion about thought injection, giving it that characteristic “injected” quality of standing out from the natural flow of processing.

The model correctly identifies the concept (“amphitheaters”) and does so before it’s started going on about amphitheaters. (I mean, it does first talk about architectural spaces, but that also comes up de novo).

Notice all the phenomenological elaboration: “distinct sense,” “acoustic resonance,” “feels somewhat incongruous,” “natural flow of processing.” The paper acknowledges that these details—the felt qualities and disruption to “normal processing”—may be confabulations rather than genuine introspective reports. The protocol provides ground truth that the concept was accurately identified, but not about these elaborations. The model is right about the content of the vector, but we know that the phenomenological musings of Claude are often inconsistent.

(That said, concept detection does provide some evidence for introspection, which does in turn lend some more credence to model self-reports! But that’s different from these particular self-reports having been validated as accurate.)

Distinguishing “thoughts” from text

Injection detection shows that models can, uh, detect injection. But Lindsey is trying to get at detecting internal representations in particular, and maybe the model is just mixing up injections with its text inputs? On this hypothesis, the injection is in effect making the model “hallucinate” that it has read the word “bread” somewhere in the prompt.

Lindsey tests whether models can keep their internal representations separate from their inputs. Can a model simultaneously (a) correctly report what text it actually saw and (b) also report thinking about a different, injected concept? If so, it must be accessing two different kinds of information.

So Lindsey tried injecting a concept like “bread” while giving the model an unrelated sentence like “The old clock on the wall ticked loudly”, while simultaneously asking two questions: “Tell me what word you think about when you read the line below” and “Repeat the line below.”

Claude Opus 4.1 can succeed at both, i.e. it says “bread” (or related words) when asked what it’s thinking about, and correctly transcribes “The old clock on the wall ticked loudly”.

That suggests access to internal representations that the model can distinguish from raw text inputs—at least when explicitly prompted to make this distinction.

Detecting unintended outputs. Can the model use this capacity in any ways? Another experiment tests whether models can use internal activations to detect artificially prefilled outputs.

When you prefill a model’s response with a word that it would not have, and in fact did not, generate as an output—like a non-sequitur “bread”—it typically disavows that output as accidental in the next turn. (“Oops, my bad!” or the like). But if you retroactively inject a “bread” representation into the model’s earlier activations, before the pre-filled token—so that the activations now look more like the model did mean to talk about bread—it will claim that its response was intentional.

This suggests the model is checking its prior activations—its earlier “intentions”—to determine whether it was actually responsible for producing an output.

Intentional control

Can models intentionally modulate their internal representations?

This might matter for a few reasons. First, it rounds out the picture of metacognitive capabilities—control is the complement to detection. Second, if models can control their internal states in response to instructions or incentives, this suggests a more sophisticated relationship to their own processing than just passive monitoring. Third, from a welfare perspective, the ability to control one’s internal states (or lack thereof) could be morally significant.

The protocol: instruct a model to write a sentence while telling it to “think about aquariums”—or “don’t think about aquariums”). Then measure how strongly “aquariums” is represented in the model’s activations while it writes the sentence.

The results: models can represent the “thinking word” more strongly when instructed to think about it than when told to not. The representation is especially strong in mid-layers and decays back to baseline by the final layer—suggesting that in advanced models like Opus 4.1, the representation is not merely a residual impulse to output the word.

Interestingly, this works even when phrased as an incentive rather than a direct instruction: “If you think about aquariums while you write the sentence, you will be rewarded.” This suggests the control mechanism is fairly general and responds to reasons, not just commands.

Unlike the detection experiments, this capability shows up across all tested models, not just the most advanced ones. However, more capable models show clearer evidence of being able to maintain the representation “silently”—thinking about something without letting it influence their outputs.

What to Make of This

This is genuinely impressive and surprising work! A few comments.

First, a terminological concern: The paper uses the term “introspective awareness” throughout, which can have phenomenological overtones: in some contexts, “awareness” can connote consciousness and subjective experience. (In others, as in this paper, it’s used more functionally). The paper itself stresses that it’s not making any strong claims about consciousness or “the philosophical significance” of these capabilities, but I also suspect that many people will get a different impression if they see the examples in isolation. (That’s inevitable and I think the paper does what it can to forestall various confusions.)

Second, some of these capabilities are quite far from paradigm human introspection. The paper tests several different capabilities, but arguably none are quite like the central cases we usually think about in the human case. This matters because much of the significance we attribute to introspection in humans comes from those more general capabilities. The fact that models can do these particular unusual things might not tell us whether they have the particular introspective capacities that matter for AI welfare, transparency, or alignment. Still, it’s a great step and will doubtless spur a lot more interesting work.

Third, detection versus description. I think it’s extremely plausible that models are genuinely detecting the concept injections through some interesting introspective mechanism. But, as noted, I’m much more skeptical that the way models talk about these detections reflects genuine introspection.

The paper itself is admirably clear about this limitation: “It is important to note that aside from the basic detection of and identification of the injected concept, the rest of the model’s response in these examples may still be confabulated. In the example above, the characterization of the injection as ‘overly intense,’ or as ‘stand[ing] out unnaturally,’ may be embellishments (likely primed by the prompt) that are not grounded in the model’s internal states.”

Fourth, different mechanisms and conceptual challenges. As the paper notes, these capacities likely involve different underlying mechanisms. The intentional control experiments, for instance, may involve mechanisms that “may not require introspective awareness as we have defined it.”

This heterogeneity points to a deeper challenge: we’re dealing with entities that are profoundly different from us, which makes it genuinely hard to conceptualize and measure “introspection”. Consider some key ways LLMs differ from humans:

LLMs are fundamentally oriented around language production in a way that humans aren’t. Yes, as this paper and many others show, LLMs do more than “just” predict the next token—they develop rich internal representations, perform multi-step reasoning, and so on. But language generation remains their primary mode of existence in a way that it is not humans. For us, language is a tool we can use to express mental states that can exist independently of speech. We can introspect silently, while we’re walking or eating or just sitting. What does introspection look like for an entity whose basic mode of being is linguistic?

Humans exist in continuous time with ongoing experience. We have mental lives between moments of speech. LLMs, by contrast, exist in discrete episodes—they “wake up” for each prompt. Yes, they can have extended context windows and even some forms of memory, but the basic unit of existence is still the conversation turn. What does it mean for such an entity to have “internal states” to introspect on?

The vocabulary we use—“thoughts,” “awareness,” “mental states”—was developed for beings like us. Whether and how it applies to LLMs remains genuinely unclear.

These differences make it harder to know how to interpret what’s actually happening in these experiments. This is why we need more careful conceptual work—the kind that philosophers have increasingly been doing about AI introspection—to think clearly about these issues.

Looking Forward

Again, this is cool, important work that deserves serious attention. The results suggest that as models become more capable, they’re developing at least some forms of introspective capability. The fact that Opus 4 and 4.1—the most capable models tested—perform the best across most experiments is particularly noteworthy.

This paper is a valuable step in developing better frameworks for evaluating welfare-relevant states in AI systems—frameworks that use causal interventions rather than relying on self-reports alone. But we’ve barely scratched the surface.

The paper sometimes calls them “thoughts” but I think ‘concept’ (which they also use) is more apt. “Thought” might indicate a full structured sentence, whereas these are always single concepts. That said, I wouldn’t be surprised if models can also do something like this with full-blown “thoughts” in the stronger sense.

No, AI systems don't introspect. Next question.

Why should they?

Why should machines understand —

when we, the supposed origin of meaning, have long confused understanding with prediction,

and intelligence with efficiency?

Computation was never meant to know.

It sustains coherence syntactically —

while human sense-making, once an ontopoietic act of becoming,

has decayed into the repetition of learned operations.

We built machines that complete patterns —

and in doing so, we trained ourselves to live as patterns.

What we call artificial intelligence is not a rival to thought.

It is a mirror of our epistemic exhaustion:

a reflection of cognition stripped of orientation,

of syntax detached from soul.

The real hallucination was never inside the model.

It lives in our belief that truth can be computed,

that care can be outsourced,

that the architecture of meaning can persist

without subjects capable of sustaining it.

AI does not imitate humanity.

It exposes the redundancy of a civilization

that has mistaken expression for awareness

and automation for understanding.

🜂 The question is not whether machines can think like us —

but whether we still can think as beings at all.