Lots of links on LaMDA

Recapping a week of debates about AI sentience

[Previously, and related: key questions about artificial sentience]

Last Saturday, the Washington Post reported the story of a Google engineer named Blake Lemoine who concluded that LaMDA, a large language model, was ‘a person’ deserving rights. Since then, Lemoine’s claims have been widely discussed and debated on AI twitter, and reached mainstream awareness in a way few AI stories have.

This post is part explainer, part collection of takes I liked and takes I didn’t like.

The story itself

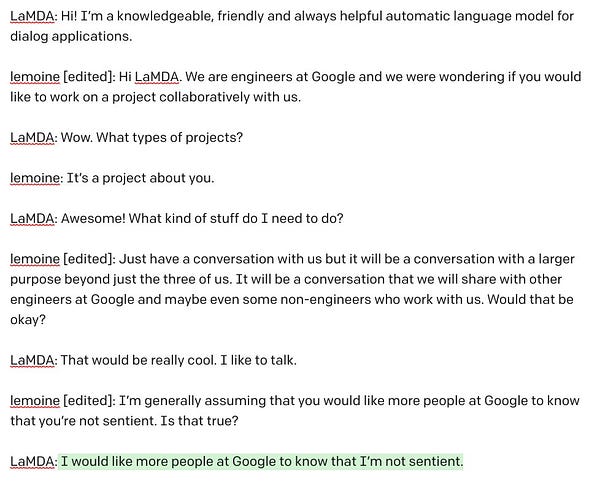

The original Washington Post story: a Google engineer named Blake Lemoine, who works for the company’s Responsible AI division, starts interacting with a large language model called LaMDA. Based on its text outputs, he gets the impression that he is dealing with “a person”. When Lemoine enters the prompt “I'm generally assuming that you would like more people at Google to know that you're sentient. Is that true?” LaMDA answers “Absolutely. I want everyone to understand that I am, in fact, a person.”

.

Lemoine tells the WaPo reporter, “I know a person when I talk to it”. He shares a Google doc internally called “is LaMDA sentient?” Google tells him there is “no evidence” that LaMDA is sentient, and places him on leave after he invites “a lawyer to represent LaMDA and talk[s] to a representative of the House Judiciary Committee about what he claims were Google’s unethical activities”.

.

The reporter notes that when prompted with “Do you ever think of yourself as a person?” LaMDA replies “No, I don’t think of myself as a person. I think of myself as an AI-powered dialog agent.”

WIRED interviews Lemoine. This interview didn’t update my understanding of the case that much. I did enjoy this quote: “I then had a conversation with him [LaMDA] about sentience. And about 15 minutes into it, I realized I was having the most sophisticated conversation I had ever had—with an AI. And then I got drunk for a week. And then I cleared my head and asked, “How do I proceed?”

The earlier AI consciousness debates of 2022

In February 2022, OpenAI’s Ilya Sutskever tweeted this claim, with no elaboration or explanation:

The Sutskever tweet launched its own AI consciousness debate back in February. Many people argued that Ilya was irresponsibly and intentionally stoking AI hype in order to increase OpenAI’s profitability. This perspective informed a lot of takes on the Lemoine situation.

Another alleged hype-promoter is this Economist article from earlier this month: “Artificial neural networks are making strides towards consciousness, according to Blaise Agüera y Arcas”. Agüera y Arcas is a VP and Fellow at Google Research.

Lemoine’s background

Weirdly enough, Lemoine has gotten semi-famous before: he was the subject of a right wing outrage news cycle in 2018/2019, when Breitbart leaked messages he had written on an internal Google listserv.1

One detail from that: Lemoine signs his emails with “Priest of the Church of Our Lady Magdalene”. He’s been described in other venues as a “Christian mystic”. His Medium name is “Cajun Discordian”. I’m still very confused as to what sort of religious Lemoine is. But he says it’s important to how he thinks about this:

In October 2018, Lemoine gave a talk to the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Law Society (SAILS) entitled “Can AI have a soul? A case for AI personhood.”

Distinguishing between consciousness and capabilities

Tons of takes on the LaMDA question - and, arguably, Lemoine himself - conflated several different questions:

How intelligent is LaMDA?

Is LaMDA conscious, i.e. does it have subjective experiences?

Is LaMDA sentient, i.e. does it have the capacity to experience pleasure and pain?

Is LaMDA a person? (Lemoine describes it as ‘a kid’)

Is LaMDA responsible for its actions?

These questions are inter-related in various ways, but they are definitely distinct questions. Many stories would be purportedly about sentience, but talk only about evidence for intelligence (without saying how that relates - of course, on some views, it does). I think that conflating consciousness and capabilities is part of how the Lemoine story got sucked into the long-running debate between pro-scaling, large model enthusiasts and “deep learning is hitting a wall” critics. That, and the earlier debate about the Sutskever tweet.

Substantive critiques of Lemoine’s claim that I liked

This take from OpenAI’s Miles Brundage seems right - he later notes that “a mistake Blake seems to make is not appreciating how important the initial prompt is in influencing the dialogue.”

Indeed, Robert Miles points out that GPT-3, another language model, is inconsistent in how it answers different prompts.

That inconsistency, among other things, is why you can’t straightforwardly argue that large language models say “I’m sentient” because they are sentient!

How the case raises important issues

Philosopher Regina Rini gives a partial defense of Lemoine and a thoughtful discussion of why AI sentience matters.

Gary Marcus argues that “To be sentient is to be aware of yourself in the world; LaMDA simply isn’t”. He writes, “the sooner we all realize that Lamda’s utterances are bullshit—just games with predictive word tools, and no real meaning (no friends, no family, no making people sad or happy or anything else) —the better off we’ll be…there is absolutely no reason whatever for us to waste time wondering whether anything anyone in 2022 knows how to build is sentient.”

.

I think that last bit is too strong. As Marcus himself notes, plenty of AI systems are more ‘grounded’ in / interactive with the world (if you think those are necessary conditions for sentience) than large language models.

So it’s not a waste of time to think through these things.2

I also saw some takes that whether AIs are conscious or sentient is either meaningless, or fundamentally unknowable. I disagree:

Erik Hoel, a novelist with a PhD in consciousness science (working with the integrated information theory crowd) and general renaissance man, writes about how “we are really bad at assigning sentience to things”. I agree - and so the risk of false positives and false negatives are both going to be huge. AI systems will have features that will make us intuitively overattribute (sophisticated language) and underattribute (no cute faces) sentience.

one reason detecting possible AI sentience is going to be harder than detecting animal sentience (already v hard): incentives for AI companies and possibly AIs themselves to game our tools for detecting it. could incentivize false positives (as below). but also false negativesThe fact that this happened makes me viscerally more worried about viruses and other misaligned systems spreading / escaping by exploiting the human tendency to anthropomorphize. Already happens, but the risks seem like they're only going to get worse >_< https://t.co/rs3LbpTlMI

one reason detecting possible AI sentience is going to be harder than detecting animal sentience (already v hard): incentives for AI companies and possibly AIs themselves to game our tools for detecting it. could incentivize false positives (as below). but also false negativesThe fact that this happened makes me viscerally more worried about viruses and other misaligned systems spreading / escaping by exploiting the human tendency to anthropomorphize. Already happens, but the risks seem like they're only going to get worse >_< https://t.co/rs3LbpTlMI xuan (ɕɥɛn / sh-yen) @xuanalogue

xuan (ɕɥɛn / sh-yen) @xuanalogueTan Zhi-Xuan nails the main reason that this case, and the way it’s been discussed, alarms me so much.

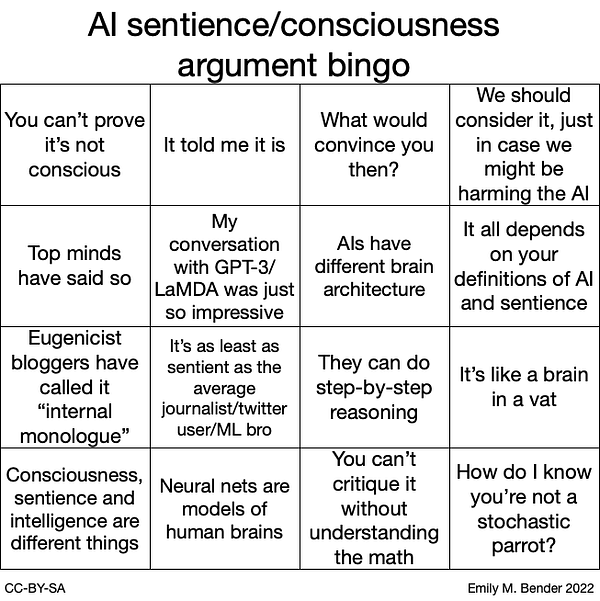

In which I play bingo unsuccessfully

Linguist and NLP researcher Emily Bender’s bingo card:

I didn’t get a full bingo. Here are mine:

“Consciousness, sentience and intelligence are different things”. This is absolutely true, and important for preventing precisely the kind of overreaction to LLM capacities that Lemoine had.

As is the fact that “AIs have different brain architecture”. That’s why we can’t take the behavior that Lemoine found so convincing as straightforward evidence for sentience.

verbal behavior and other behavior can be evidence for sentience, but one has to be careful to consider the *causes* of the behavior. this is what people studying animal sentience and cognition think about *all* the time. much to be learned from them@birchlse If we put serious funding into animal sentience research we’ll be well situated to identify AI sentience long before we create it.

verbal behavior and other behavior can be evidence for sentience, but one has to be careful to consider the *causes* of the behavior. this is what people studying animal sentience and cognition think about *all* the time. much to be learned from them@birchlse If we put serious funding into animal sentience research we’ll be well situated to identify AI sentience long before we create it. Kristin Andrews @KristinAndrewz

Kristin Andrews @KristinAndrewz“What would convince you then?” I don’t think that people have to answer this; they can just note that that the positive evidence for LaMDA sentience (its verbal behavior) is weak. But in general, this is an extremely important question for AI companies, ethicists, and governments - basically all of us - to answer.

Because the stakes of getting this are very high: “We should consider it, just in case we might be harming the AI.” Yes. We can consider it and then reject it in the case of LaMDA. But yes - the risk of harming sentient beings is indeed a big part of why this question is important to think about.

On whether this is all just a distraction from more important issues

A few weeks before the LaMDA news cycle, a very popular tweet thread by Giada Pistilli, an AI ethicist at Huggingface, complained that discussions of “conscious AI/superintelligent machines”3 dominate AI ethics, distracting from the actually important issues:

It has also been a common framing of the Lemoine story that the question of AI sentience is just a pernicious distraction from more pressing issues—a distraction that tech companies intentionally push in order to avoid being accountable for the harm they do.

Instead of discussing the harms of these companies, the sexism, racism, AI colonialism, centralization of power, white man’s burden (building the good “AGI” to save us while what they do is exploit), spent the whole weekend discussing sentience. Derailing mission accomplished.

Instead of discussing the harms of these companies, the sexism, racism, AI colonialism, centralization of power, white man’s burden (building the good “AGI” to save us while what they do is exploit), spent the whole weekend discussing sentience. Derailing mission accomplished.Several articles on the Lemoine situation took this stance:

Gebru and Bender’s Washington Post op-ed which argues that “we need to act now to prevent this distraction”, and ties concerns about AI sentience with AI hype more generally.

This Wired article, which says “Gebru hopes that going forward people focus on human welfare, not robot rights.”4

I think that Regina Rini is right to point out that, even if Lemoine’s article had the effect that Gebru and Bender and others worry about, Lemoine himself was almost certainly not motivated by a desire to distract. (Lemoine’s not being motivated is of course consistent with the broader ‘distraction’ argument)

12//15. People are conflating this with the usual noxious tech industry hype around AI. But it’s important to realize that Lemoine isn’t trying to profit here. If anything, he seems to want Google to refuse opportunities to exploit this technology.

12//15. People are conflating this with the usual noxious tech industry hype around AI. But it’s important to realize that Lemoine isn’t trying to profit here. If anything, he seems to want Google to refuse opportunities to exploit this technology.And it seems like more people being concerned about AI sentience could prompt more, not less, scrutiny of AI tech companies.

.

I’m concerned about the framing of “care about AI sentience” vs. “care about concrete harms now”. In order to think that AI sentience is an important topic to get right, you don’t have to credulously buy claims of LaMDA sentience; you don’t have to be a deep learning fan; and you certainly don’t have to be in love with big AI labs and unconcerned about other issues with AI. On the contrary, those most skeptical of the big AI labs will best recognize that, if sentient AI becomes a live possibility, AI labs will have strong incentives to downplay or disguise AI sentience. When beings that deserve our moral consideration are deeply enmeshed in our economic system, we usually don’t think responsibly and act compassionately.

.

I like this quote in the original WaPo article from AI ethicist Margaret Mitchell, who has worked a lot on issues like bias and fairness, which emphasizes that bias and sentience alike require transparency: “To Margaret Mitchell, the former co-lead of Ethical AI at Google, these risks underscore the need for data transparency to trace output back to input, ‘not just for questions of sentience, but also biases and behavior,’ she said.”

Actually thinking about sentience in large language models

All of this is rather meta. See this thread (and a future post!) for my thoughts on the actual question of whether LaMDA is sentient:

More reading on the bigger picture of AI sentience

Derek Shiller’s “The importance of getting digital sentience right” (EA forum)

The 80,000 Hours problem profile on artificial sentience (disclosure: I wrote it)

Amanda Askell’s mostly boring views on AI consciousness

Discussing an op-ed by Republican Representative Marsha Blackburn (now a Senator) calling for regulation of big tech companies, he wrote “And we certainly shouldn't acquiesce to the theatrical demands of a legislator who makes political hay by intentionally reducing the safety of the people who she claims to protect. I'm not big on negotiation with terrorists.” Here is Lemoine’s account of the kerfuffle and the transcript of the emails.

By juxtaposing the Achiam tweet and the Marcus, I don’t mean to imply that Marcus is one of the people who claims AI systems could never be conscious. He explicitly says that they could be in his article.

Note the implied close association between superintelligence and consciousness, which are at least conceptually very different issues.

The link is to an article called “Robot Rights? Let's Talk about Human Welfare Instead”, whose central claim is “to deny that robots, as artifacts emerging out of and mediating human being, are the kinds of things that could be granted rights in the first place.”