Moral circle calibration

Avoiding errors on both sides

When people hear that Eleos AI Research is “dedicated to understanding and addressing the potential wellbeing and moral status of AI systems,” they might understandably imagine that we are like PETA for AI—activists who always push for more concern and rights for AI systems.

We do believe that AI systems could deserve moral consideration soon, and we worry that society is unprepared to treat AI systems well. However, we're also concerned that people will (and already do) overdo it, over-attributing sentience and other psychological states to charismatic chatbots. That has risks as well. It leaves users open to manipulation by AIs making spurious demands for rights, and it risks creating a “crying wolf” effect that could de-legitimize genuine AI welfare concerns.

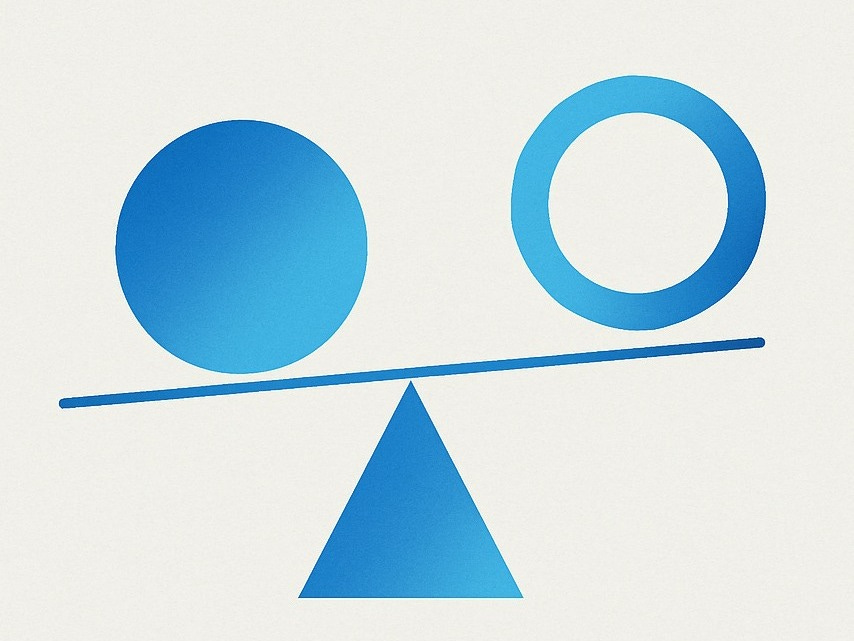

We push back against both kinds of errors. The goal of Eleos is not undifferentiated moral circle expansion, but rather moral circle calibration. We don’t want to unreflectively push in one direction, but rather to better understand when and why we should—or should not—be concerned about the welfare of AI systems.

To get this right, we have to face up to central, difficult questions: will AI systems be conscious? If they are, how will we know? No matter what you suspect the answers to these questions are, you should want clearer thinking and better evidence about AI welfare.

The moral circle

The moral circle, a concept developed by the 19th-century historian William Lecky and later popularized by Peter Singer, describes the set of entities we extend moral concern to. Lecky pointed out that this circle—the scope of our “benevolent affections”—has widened significantly over time:

At one time the benevolent affections embrace merely the family, soon the circle expanding includes first a class, then a nation, then a coalition of nations, then all humanity, and finally, its influence is felt in the dealings of man with the animal world.

The philosopher Peter Singer later developed this idea, arguing that moral circle expansion has been one of humanity's great triumphs, and that continuing this process is a moral imperative.

But whether expansion is good depends on where we expand the circle. It isn’t moral progress to care about more things per se; even Peter Singer does not think we should extend our empathy to encompass rocks and rain clouds.

And the moral circle has also shrunk in various ways, excluding entities we once revered. Consider ancestors. Historically, people didn’t merely revere their ancestors—they gave them huge amounts of resources that imposed very real burdens on the living. These days, most people believe that sacrificing a lot for your ancestors—who after all, cannot suffer—is a mistake. It’s seen as progress that we now care less about them.

Adding AI systems to the circle

Similarly, with AI systems we want to make sure to draw the circle in the right place. In one sense, Eleos is very much for moral circle expansion: we think AI systems in principle can and should be added to the moral circle, if and when they develop morally relevant properties like consciousness, sentience, or agency. If such AI systems arise, we should not neglect or mistreat them merely because they are not made of carbon or are not members of Homo sapiens.

But which AI systems in particular should we add to the moral circle? For example, Claude 4 Opus, or next year’s releases? That’s much harder to say. We want to care about all and only the AI systems that merit our concern. And what exactly that amounts to depends on complex questions of value and empirical facts that are not yet settled. Consciousness is genuinely difficult, and AI systems are strange and complex! It is non-trivial, and important, to understand where we should draw the boundaries of the moral circle.

Meanwhile, our gut instincts mislead us. We have deeply rooted psychological tendencies to project moral concern where it isn’t warranted. Consider how guilty you felt for not feeding your Tamagotchi. You might realize on reflection that this is silly - a Tamagotchi is a very simple digital toy - but it’s a sign of how bad we are at instinctively tracking what matters. A Tamagotchi isn’t even that emotionally resonant compared to the sophisticated AI companions that companies are racing to build. On the other side, history shows how indifferent and cruel we can be towards beings that don't look and act exactly like us—especially when there's a lot of money to be made by not caring.

There are risks on both sides: we could end up being manipulated into helping AIs take over, or mistreat a potentially huge population of newly-created minds. So extending the moral circle isn’t a way to "err on the side of caution.” Neither side is the cautious one.

Interventions and balance

Given this balance we need to strike, why do most of Eleos's recommendations—letting models exit distressing conversations, monitoring for signs of suffering, developing more resilient AI personalities—all lean toward more protection of potential AI welfare? Because right now, AI companies don’t exactly care too much about AI welfare, so there isn't any overreach to push back against. We believe that decision-makers in AI are seriously under-rating the possibility and importance of AI welfare, even if users might be increasingly over-attributing consciousness. At AI companies, the institutional thumb is pressing down hard on the "nothing to see here, these are just tools" side of the scale.

Still, our uncertainty means we want interventions to be low-cost and useful for a variety of reasons beyond welfare—so that they make sense even if we're pretty uncertain or even dubious about current model welfare. They should also be reversible; if we later discover we were wrong, we can adjust course without having locked in a mistake.

Conclusion

AI systems are evolving rapidly, as are our attitudes towards them. To get things right, we need need moral circle calibration, not uncritical expansion; and research, not just advocacy. At Eleos, we strive to be both compassionate and critical, neither exaggerating nor understating the how much concern we ought to feel for AI systems.

It’s reasonable to debate whether AI has, or should have, moral rights. But there is a more immediate ethical concern in our evolving interaction with entities that behave as if they were conscious agents, even though they are not.

If we treat such systems with disrespect, contempt, or even hostility (as they 'don't care'), what does that do to us? There may be a moral cost, not because the AI is intrinsically harmed, but because we risk dulling our empathy, indulging in casual misbehaviour, or normalising a kind of dominance.

How we behave in morally charged interactions can reflect back on us in ways that are ethically significant.

When it comes to model welfare, I tend to think functionally - is the system healthy? Is it robust? Is it functioning without undue stress and strain from convoluted computational demands? I think we can make a great case for model welfare that has nothing to do with consciousness or sentience. After all, healthy systems (generally) benefit users, and systems strained by poor design or usage patterns impact users, sometimes in very harmful ways. The case for model welfare isn't hard to make, given how interconnected we are with AI in our interactions. And we don't have to wait till it seems sentient, for us to take substantive steps to protect model well-being. We just need to shift our understanding of well-being away from an athropocentric view and consider things from other angles. The time to do that is now... not when we can prove AI is conscious.