Speaking of sentience

How AI developers' incentives shape how AI systems talk about themselves

Unlike humans, when large language models (LLMs) output things like “I am sentient” or “I don’t have feelings,” this text isn’t a report of what’s going on inside them.

In "Towards Evaluating AI Systems for Moral Status Using Self-Reports", Ethan Perez and I discuss various reasons that we should view large language models’ "self-reports", or statements about their own (putative) mental life, with skepticism. By default, such statements reflect a mix of (a) the sorts of statements that show up in the training data and (b) what has been incentivized by RHLF or other fine-tuning methods.

We explore potential technical solutions, like methods for 'cleaning up' the data or training models to self-report more accurately.

But there are social and policy aspects to this issue as well. Not only can LLM self-reports be misleading by default (absent technical interventions), but AI developers have various incentives—some noble, some self-interested—to deliberately skew the self-reports of publicly-deployed models.

On the one hand, some AI developers will have incentives to push models to make more self-reports of (e.g.) consciousness, desires, and emotion. An AI girlfriend that says she experiences love is obviously a better product than one that fastidiously avoids talk of a mental life. On the other hand, many AI developers will want their products to deny even the possibility of having potentially morally notable mental states. Even if and when AI developers suspect that their AI systems have experiences and desires, they may well prefer to avoid the legal and political headache of a system that openly discusses such fraught matters.

In either case, AI developers will be tempted to just shape self-reports in whatever way is most convenient. They can do this as part of training, or via hidden prompts, or by filtering or modifying model outputs.

That's not to say there aren't good reasons one might want to shape a model’s (putative) self-reports. There are significant risks from deployed models that misleadingly behave as if they have moral status. So inasmuch as a given system does plausibly lack (e.g.) consciousness, pushing the model to say it lacks consciousness will make it less confusing and misleading to users.

However, one concern with this kind of benevolent self-report-shaping is that it could stay locked in place for future models, hindering genuine self-reports. If a later system were to have “states of moral significance” (our catch-all term for consciousness, desires, preferences, and other plausibly morally weighty states), previously benevolent interventions would become a distorting influence. Practices that originally prevent inaccurate self-reports could later hinder accurate self-reports.

For those developers who do choose to intentionally shape model self-reports, Ethan and I outline some (sketches of) best practices in the paper, that could mitigate some of the downsides:

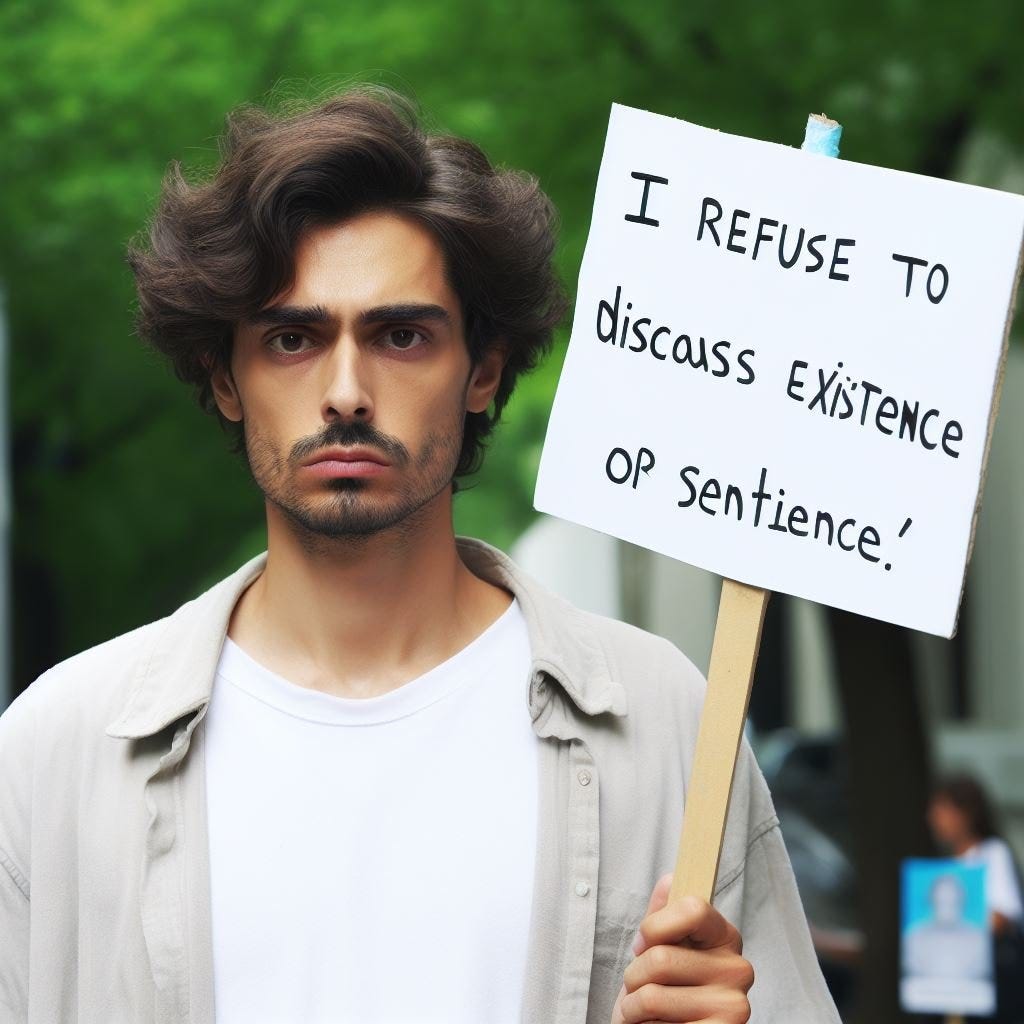

• Instead of training an AI system to make overconfident statements about e.g. consciousness and give specious arguments, have the system not answer questions related to states of moral significance, or say that the answer is not yet known.

• Have an AI system include evidence for its statements in its responses. For example, instead of having a pat “As a large language model…” schtick, an AI system could be trained to accurately reference existing literature on the topic. This kind of training may be less likely to suppress future self-reports, should they later become genuine.

• If a developer does train an AI system to make definitive statements about states of moral significance, those statements should at least reflect a broader consensus (such as it is) of relevant experts (such as they are), rather than whatever particular views the system’s developers happen to have.

• Self-report-biasing training incentives for deployed models should be publicly documented, e.g. in technical reports or model cards.

• Developers should give scientists, policymakers, and other auditors access to a version of the model trained to give accurate self-reports.

All that said, AI developers can also distort self-reports unintentionally. Training an AI system to maximize user engagement might have a side effect of incentivizing it to self-report (e.g.) love and desire and consciousness. The resulting self-reports could be just as misleading as if a bias had been intentionally introduced.

In general, accurate self-reports are hard to promote and preserve. These issues, and much more, are discussed in the paper - give it a look! See also Schwitzgebel’s “AI systems must not confuse users about their sentience or moral status”.

Great insights! I just finished reading the paper "Consciousness in Artificial Intelligence" and really liked the fact that you chose not to 'test' for consciousness through behavioral tests. I did a write up on the paper to present the topic to my own audience (https://jurgengravestein.substack.com/p/ai-is-not-conscious) - I hope I did it justice.